Tuesday, December 31, 2013

Wednesday, December 25, 2013

Friday, December 20, 2013

This is about Astral Weeks; this is not about Astral Weeks

In what is possibly the most edifying commencement speech of our time, David Foster Wallace sketched out a rough outline of adulthood for Kenyon College's Class of 2005. Middle age's defining battle will not take place in the home, the workplace, or a fast-food drive-thru line. No, according to Wallace, this battle will take place inside us, for surviving those middle years is predicated upon whether or not we can muster the strength to "stay conscious and alive in the adult world day in and day out" and endure the "large parts of adult American life that nobody talks about in commencement speeches ... boredom, routine, and petty frustration." Wallace, I should mention at this point, hung himself when he was 46.

When I was the same age as the graduates Wallace enlightened, I freelanced for a variety of local weeklies. On deadline nights, I hung around the office of my old college newspaper, chatting with friends who had yet to graduate, extolling them on the merits of a career in the newspaper industry (this was 1996—things were grand). I drank cans of cheap domestic beer, hammered out countless inches of freelance copy, and dispatched stories to my editors via the newspaper's fax machine. I wrote drunk, but only because the banality of high school sportswriting demanded I do so.

One night, I drove a friend from the office to his apartment in Brighton. If Hollywood has taught us anything, it's that terribly profound heart-to-hearts generally take place in automobiles, so as we rode through Boston—orange streetlights dancing across the windshield, our faces masks of shadowy tension, the song on the radio echoing our conversation—we chatted about post-college life and the transition into adulthood. The phrase "Please kill me if I am still hanging at the college newspaper in 10 years" was heard more than once; we lamented our lack of decent job prospects. This is what we primarily discussed: failure—how it would take shape, when it would confront us, what it would feel like to be utterly squashed by it. Because when you're awarded that freshly embossed diploma and endlessly alerted to the certain triumphs and trophies that await you, it's inevitable that you start dwelling on what goes unspoken, what is entirely disregarded, what lurks in the darkness ready to pounce: All that you dream of one day accomplishing may remain just a dream.

Last week, as I sat in my car in our office parking lot, an adjacent truck slowly inched backwards and for an instant, there was the illusion that I was moving forward even though I was stationery—a metaphor not lost on me. James Salter, who penned one of my favorite books that I read this year, wrote the following sentence in his latest work, All That Is: "There comes a time when you realize that everything is a dream, and only those things preserved in writing have any possibility of being real." This is Salter grimly recognizing that life is alarmingly fleeting and a recurring setting for the unimaginable—that failure to leave our own unique mark on the world is the most terrifying failure of all, one you never considered when engaging in late-night heart-to-hearts in automobiles in your twenties.

So I heed the words of individuals like Wallace, who point the way out of this middle-age tangle—one where I am moving forward without moving at all. Be free, Wallace advises, be conscious. The world is in front of you and behind you and all around you—seize it, scrutinize it, savor it. Pursue the kind of freedom that's centered on knowledge and passion. And get cracking on that legacy: a piece of art, a piece of writing, a piece of music, anything that incorporates a piece of yourself.

Thursday, December 19, 2013

"Will you come back tomorrow?" I said sure.

This quote is from Clinton Heylin's Can You Feel the Silence? It's a particularly crucial moment from Astral Weeks' lengthy gestation. Upright bassist Tom Kielbania, who had recently started pairing up with Van Morrison for live shows, heard flautist/saxophonist John Payne during a Boston-area jazz session. Kielbania then invited Payne to play with him and Morrison down at the Catacombs. Said Payne:

Tom [Kielbania] came out [and said to Van], "Oh, this is the flute player I talked to you about." ... He looked up ... and seemed not irritated, not negative, but just ... not there—not warm at all ... So I didn't feel that good. He didn’t say, "Oh, how are you doing?" or anything ... So I heard the first set, and I didn't like it ... I thought of leaving but ... just kind of hung around ... And then Van came out just before they went on [for the next set], and said, "Do you want to sit in?" And I went, "Oh, sure." So I went up there and he started singing the first number, and I listened for a while and then came in. Even before I came in, I could tell this was a singer of a caliber I had never played with before. But I couldn't feel this from the audience ... because this wasn't my thing ... But once I was up there I could really feel [that] this was ... just coming from a much deeper place ... I started playing with him and I noticed he would react to what I did. I mean if I played something, he was listening to it. I'd never played with a singer who was paying attention to what I did, [such] that I could notice ... So at the end of the first number I was like, "Wow, that was great." And the second number he does is "Brown-Eyed Girl." And he starts singing it, and I knew that song. I didn't know whose it was, but I'd heard it around, you know ... And I suddenly [realized] he isn't covering somebody's song. This is his song ... That night he offered to pay me—and they were making almost nothing. The crowd was thirty people, maybe ... [but] he offered to pay me a few bucks out of the take, and I said, "No, no, I just sat in." [Then] he said, "Will you come back tomorrow?" I said sure.

Friday, December 13, 2013

Fluid interpretations

Van Morrison, talking to Los Angeles Times columnist Randy Lewis about Astral Weeks: "The songs are works of fiction that will inherently have a different meaning for different people. People take from it whatever their disposition to take from it is."

Different meanings for different people ... For me, interpretation of Astral Weeks is fluid; what a track signifies or suggests oftentimes changes after repeated listens. "Astral Weeks" presently feels like it's about making peace—both with yourself and with the past. Morrison opens by singing, "If I ventured in the slipstream." His voice is confident and full and slightly tender. When he sings these words a second time, at the track's 3:36 mark, Morrison sounds noticeably different. His voice is slightly higher; he draws out the syllable "stream," putting emphasis on the long e sound. He is desperate, agitated, a touch world-weary.

The first "If I ventured in the slipstream" feels rehearsed—it conjures images of Morrison standing in front of a mirror, fine-tuning a prepared speech for a bygone love, testing words out loud. The second feels like a release: Fortune has presented him with an opportunity to finally deliver his words to the intended recipient; the emotional weight from carrying them is lightened. An eternity has elapsed since he bid her farewell, yet some essence of their love remains. But this isn't about pursuing a reconciliation or even a reckoning. Morrison's breathy allusions to rebirth ("In another time / in another place") make his intentions clear. He is asking his bygone love this: If given another go-round on this here spinning rock, would they try again?

Tuesday, December 10, 2013

"The past is never dead; it's not even past"

I recently stumbled upon a quote that said in Hollywood success doesn't begat more success; instead, it instills a deep and profound terror of failure. The music industry has long been mired in a similar limbo of its own making. A kind of stasis where songwriters are emboldened to produce marginal recreations of previous material, where explicitly rejecting commercial norms is anathema to industry rules. "The past is never dead; it's not even past"—bold those words, splash them with color, and slap them across the back of a record exec's business card.

So how do these sins get absolved? By disregarding mindsets that consider "not losing" and "winning" to be similar objectives. By accepting that what is safe is also tame. By understanding that songwriters who stubbornly refuse to bend their art to the mainstream demands of the era should be glorified. By taking a young Irish lad who had just scored a Top 10 hit and recorded a rather middling MOR debut album, and dropping him into the recording studio with musicians like the jazz drummer featured in the above video. Ballsy moves like that are rare, no?

Saturday, December 7, 2013

A different theory

A tiny addendum to my Dec. 2 post regarding the genesis of Moondance. Since Astral Weeks was the music equivalent of a big-budget blockbuster becoming a box-office flop, Van Morrison was compelled to stride down a more commercial path. "I was starving. Practically not eating," Morrison said years later—very likely unaware of how an Irishman discussing hunger in any context always lends extra gravity to their words. At any rate, the postscript is this: Maybe Morrison's eagerness to separate himself from Astral Weeks was partially because Northern Ireland's rapid descent into sectarian violence took place in the aftermath of the album's release.

His beloved homeland—a place of eternal innocence and allure that was immortalized by his album—was forever altered. How could listeners from that time period hear "Madame George" and not wonder if the Troubles affected the colorful places he evoked and the dreamlike atmospheres he created? Where they spoiled by bomb or bullet? Would Northern Ireland ever be the same? So perhaps it wasn't just a desire to move more records that inspired Moondance, but his disgust, disillusionment, shame—maybe even genuine heartbreak—over what was occurring back home.

(Quick aside: The Troubles' harrowing opening act took place during the 10 days in-between Astral Weeks' final two recording sessions at Century Sound Studios in New York City. On Oct. 5, 1968, a civil rights march in Derry turned violent when the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC), Northern Ireland's now-defunct police force, boxed in the crowd of 400 demonstrators at Duke Street and baton-charged them from two sides. Those who broke free were driven across Craigavon Bridge with water cannons. [According to Tim Pat Coogan's book The Troubles: Ireland's Ordeal 1966–1995 and the Search for Peace, the first use of a water cannon in Northern Ireland.] An estimated 90 to 100 demonstrators were treated for injuries. The RUC reported none. Thanks to an RTE cameraman, who was at the scene in Derry filming, pictures of RUC brutality flashed across the globe. One of the most shocking and enduring images was of a bloodied Westminster MP Gerry Fitt, who suffered a head injury from several baton strikes.)

Tuesday, December 3, 2013

I like granola bars

I've found middle age to be a rather lonely proposition. The everyday grind of employment/family/homeownership leaves me feeling cut off from friends, acquaintances, and various others who fall somewhere between "well-wisher" and "mildly supportive ally." There is so little precious time. I spend approximately 6 1/2 hours in a car each week commuting to and from the office. This is generally 6 1/2 more hours than I spend in a social setting chumming it up with other members of my species. This is troubling; the inside of an automobile is quite confining and sarcophagus-like. And there are no beer taps.

What I've also discovered is that middle age is beautifully cruel in its ability to flat-out deflate you. Personal ambition gets squashed by reality. Small defeats are magnified. A carefully constructed legacy is toppled. One morning you rise and shower and eat a granola bar and peck your wife on the cheek, and then realize that every bead of hot water, every shard of granola, and every kiss-induced drop of saliva makes up the tiny filaments in what is the rich tapestry of your boring fucking life.

Over the past few years, I have gravitated toward a pair of albums that explore themes heavily associated with middle age: Yo La Tengo's And Then Nothing Turned Itself Inside-Out and the Wrens' The Meadowlands. As I once wrote elsewhere, the former articulates "what it feels like to walk through life consciously unconscious," while the latter acknowledges that "even when you write as if your words are eternal, everything you create can still be forgotten and ignored." It sounds dispiriting, sure, but it can also spur much-needed reflection. Reflection that's somewhat like staring close-up at your hairy-eared, grey-bearded, crow's feet-addled visage in the bathroom mirror.

This may sound odd, but I consider Astral Weeks to be a record equally steeped in middle-agedness, even though it was composed by a man in his early twenties. But it's also become a frequently more difficult listen. Astral Weeks' propensity for gazing affectionately at the past, at the ebb and flow of adolescence, at days that are gone forever creates a helplessness that lingers. I'm stuffed with an infinity of memories, yet left feeling all hollowed out inside. Those aforementioned records inform middle-aged folk of what we have become; Astral Weeks hints at what we've become while reminding us of all that we have lost. Pass the granola bars.

Monday, December 2, 2013

Futebol d'arte vs. futebol de resultados

I'm reading Inverting the Pyramid, Jonathan Wilson's in-depth history of football—er, soccer; so sorry—tactics and formations. Connections between Astral Weeks and the sport of soccer are nonexistent. (Though I find it slightly fascinating that around the time Van Morrison was at the top of his game, a fellow Belfast native was reaching similarly lofty heights in English football.) Nonetheless, one of Wilson's early observations permeated the Astral Weeks-dominated portion of my brain: "The tension—between beauty and cynicism, between what Brazilians call futebol d'arte and futebol de resultados—is a constant, perhaps because it is so fundamental not merely to sports but also to life; to win or to play the game well?"

Sheer beauty or glittering prizes? Art or results? Which will it be? One must be sacrificed to produce the other. Following Astral Weeks, Morrison abandoned the unrestricted boldness and expressive individualism of his masterpiece for a more pragmatic (read: commercial) approach. Consider this 1986 quote found in Clinton Heylin's Can You Feel the Silence?: "[Astral Weeks] was a success musically and at the same time, I was starving. Practically not eating. So for the next album I realized I was going to have to do something [that sounded] like rock or [continue to] starve ... So I tried to forget about the artistic thing because it didn't make sense on a practical level. One has to live." Or this, from Johnny Rogan's Van Morrison: No Surrender: "I make albums primarily to sell them and if I get too far out a lot of people can't relate to it."

The result was Moondance, a collection that certainly ranks among Morrison's best, but one that also reveals an artist becoming self-conscious about being too self-conscious. Moondance is more concentrated, more compromising, more devoted to efficiency and discipline. It's evidence that proper self-control is the swiftest path to the Top 40. It's Morrison's I-need-to-eat album—an LP akin to comfort food. Astral Weeks is the more meaningful and eternal release, but also confirmation that even the most enduring pieces of art typically don't pay the bills.

Tuesday, November 26, 2013

Remix unleashed, unleashed remix

Jim Adams, who uploads tracks under the username Jimdubtrix on Soundcloud, unleashed this remix of "Madame George." It's titled "Get on the Train" and it's got this jazz/electro-soul/dub/trip hop/ambient lounge thing going on. It covers a lot of genre ground, but doesn't wander aimlessly. It's inventive and sonically exploratory, yet remains true to the original. It's a rightful homage that doesn't fall prey to being worshipful.

Friday, November 22, 2013

A sunken city

"Beside You" is my least favorite track on Astral Weeks. I'm tempted to say that it's doubtful the song's position as such will ever change, but this is Astral Weeks. A significant portion of the album's allure is wrapped up in its sheer bulk, its wondrous impenetrableness, its capacity to reveal a glittering new particle of genius with every listen. I've played Astral Weeks 1,000 times now—maybe "Beside You" will click on that 1,001st listen.

Anyway, for all the track's sins—it's slightly aimless, scattered with awkward imagery (when's the last time you heard a song reference nostrils?), and on an album stuffed with dense instrumentation, the stripped-down production leaves it feeling vacant and unfinished—I do relish Van Morrison's vibrant, meandering allusions to the beauty and grace of the physical world: "And you wander away from your hillside retreated view," followed by, "Way across the country where the hillside mountains glide."

Morrison's words were sparked by his eternal affection for his home (which is the case for much of the lyrics on Astral Weeks, of course)—in this particular instance, Belfast's striking natural beauty. Gerald Dawe dutifully described it in his book My Mother-City: "Coming into Belfast is like approaching a sunken city. It lies inside a horseshoe of surrounding hills; the coastal land to its southern shoreline is the rich, undulating landscape of County Down; to Belfast's northerly shores is Country Antrim: a harsher, dramatic terrain that faces Scotland across the narrow straits of the sea of Moyle."

And as I once wrote for One Week // One Band:

In Belfast, the serenity and relief of the countryside is always within one's grasp; you can hop in an automobile and drive from the city center to the base of Divis, a mountain that looms to the northwest, in roughly 20 minutes. The allure of that serenity and relief is inescapable. During our trip to Belfast, we took a morning walk up the Lisburn Road from our rented flat on College Gardens and I noticed how each glance down a narrow side street offered breathtaking views of the nearby mountains.

Wednesday, November 20, 2013

Soft and hard emotion

On Sunday afternoons, May Kelly's Cottage hosts a weekly seisiun. For those not blessed with the divine ability to communicate in the Irish tongue, seisiun simply means "session" and it denotes those informal pub gatherings in which musicians assemble to play traditional Irish songs. May Kelly's weekly seisiun is a heavily-attended event. You arrive early if you wish to sit. Your ears buzz from the cacophony of fiddle, button accordion, and bodhran, and clapping hands and chattering voices. And when those four pints of Smithwick's demand an immediate departure, you inadvertently step on feet and jostle elbows as you maneuver through dense herds of humanity.

One Sunday, a man with a head like a pencil eraser and a chassis few could wrap both arms around sang "The Leaving of Liverpool" and when he neared the final rendering of the chorus he began to slowly amble backward toward the room's entrance and after belting out the tune's closing phrase he swept one arm in an exaggerated good-bye flourish and quickly departed, hearing only the start of what was raucous applause for his performance.

And on another Sunday, a man brought a double bass to the seisiun. The effect of seeing such an instrument at such a gathering and in such a setting was like watching a rickshaw mosey up to the starting line at the Indianapolis 500. When I saw the man with the double bass enter a room where the weighty burden of Irishness being hefted by countless listeners was practically palpable (burdens both real and imagined), I couldn't help but think of Richard Davis and the weighty burden of Irishness he encountered when he walked into Century Sound Studios in New York City.

Davis is responsible for the most compelling instrumentation on Astral Weeks. His basslines are so smooth, so melodious, and so pure that you almost fail to notice his achievement. But that was possibly his goal. Davis' bass is the soft emotion that rests beneath the hard emotion of Van Morrison's vocals and acoustic guitar—Morrison expresses power while Davis suggests vulnerability.

Davis is also responsible for one of my favorite quotes regarding Astral Weeks. In a Rolling Stone piece the bassist discussed the album's twilight recording sessions: "There's a certain feel about a seven-to-ten-o'clock session. You've just come back from a dinner break; some guys have had a drink or two. It's this dusky part of the day and everybody’s relaxed. I remember that the ambience of that time of day was all through everything we played."

Saturday, November 16, 2013

Shirtless

So this one dude covers "The Way Young Lovers Do." He's standing in his well-furnished living room and he's wearing freshly ironed slacks and judging by the light coming through the curtains, it's the early afternoon. You know what happens in the early afternoon? Newspapers are delivered, gutters are cleaned, kids come home from school, housewives sip coffee and lick the moisturized tips of their index fingers and flip through newspaper flyers. The bright, bland light of early afternoon is no time to be singing about the way young lovers do this, that, and the other thing. So I found the dude seen above. He's got his shade pulled down; it's dark outside. Young lovers thrive in the dark. Listen to him turn the pages in his songbook. He's suffering from romantic agitation. Or maybe he's aroused and the sexual energy has seized his fingers. Plus he's shirtless! Shirtless is part of the young lovers' dress code. In fact, I bet Van Morrison was shirtless when he wrote the song in his Belfast bedroom.

Wednesday, November 13, 2013

"What difference does it make where you were born?"

Van Morrison was recently presented the Freedom of Belfast Award (only the second person in 10 years to receive the accolade). He spoke glowingly of his native city. On Friday, he will play a free concert at the Waterfront Hall in Belfast. When considered separately, these events range from momentous to relatively unremarkable. Taken as a whole, they are evidence that it's possible to reconcile a troubled past with a promising future. (This relates to Morrison's relationship with Belfast, but could also reference the relationship between the city's religiously divided communities.)

Strong are Morrison's current ties to Belfast—ties forged by: a decade-long creative burst in which he churned out some of the most intensely autobiographical compositions of his career (two of the better numbers from that time: "Cleaning Windows" from 1982's Beautiful Vision and "Coney Island" from 1989's Avalon Sunset); a willingness to highlight live performances from Northern Ireland (1984 release Live at the Grand Opera House); a request to assume a small role in the peace process (the title track from Morrison's 1995 album Days Like This was used by the Northern Ireland Office in an advertising campaign promoting the Good Friday Agreement). So strong are these ties that it's virtually impossible to recall the extended period when Morrison was estranged from his home.

Soon after the release of "Brown Eyed Girl" in July of 1967, the singer-songwriter left Hyndford Street for the U.S. He took an extended tour of the Republic of Ireland in 1973 and embarked on trips to Dublin in the following months, but Belfast was never on the itinerary (much to the dismay of fans and the irritation of music journalists). For 12 years Morrison shunned Northern Ireland; his self-imposed exile didn't end until February of 1979, when he played a pair of shows at Belfast's Whitla Hall. During his time away, Morrison's public comments about his home were typically tinged with apathy and displeasure. One oft-repeated quote: "What I'm not part of is the hatred thing. What difference does it make where you were born? It's just a piece of land. All I can say is that I'm neutral."

How Morrison was able to speak negatively about his birthplace in sit-downs with newspapermen while venerating Northern Irish places in his art is several hundred words for another day. (In short, Morrison firmly believes that the seemingly innocent Belfast of his adolescence and the violence-ridden Belfast of The Troubles are two wholly and distinctly different places. One has zero to do with the other. And thanks to the Good Friday Agreement, which has delivered a period of relative peace and prosperity, Morrison can draw parallels between present-day Belfast and the Belfast of his bygone years. That's my theory at least.) What can be stated is that Morrison's reverence for his home has never been so profound and undeniable. For a long time, it felt like the nickname "the Belfast Cowboy" was waiting to be taken up and dressed in, that Morrison's long absence from the city meant the moniker wasn't quite his to wear. Today, that's all changed. Today, the name fits snugly.

For the Belfast Cowboy, the word place is no longer something physical that is perceived by the senses. It's become something constructed through experience, something shaped by memory and emotions, something to be carried around internally, now and until the end of his days. It took leaving Belfast for him to realize that Belfast will never leave him.

Friday, November 8, 2013

"This is THE WORST place"

The door to 1120 Bolyston Street is locked. Wait long enough, however, and someone inevitably approaches with a key to enter. (The amount of constant entering and exiting is what initially urged my accomplice—who works nearby, but has never set foot inside 1120 Bolyston—to assume that the door was always unlocked or didn't sport a lock at all.) We sneak in behind a key-toting gentleman, step slowly down a long flight of stairs. At the bottom is a snaking, dimly-lit hallway haphazardly painted in shades of burgundy and cream. There are numerous doors off the hallway; each one is numbered and shut tightly. These are the rehearsal spaces Doug Ferriman mentioned in his email, spots where Berklee College of Music and Boston Conservatory students come to refine their skills. As we walk down the hallway, the din emanating from behind the doors is overwhelming. A drummer works on heavy fills, a guitarist brashly repeats a few chords, a saxophonist plays shrieking runs. It sounds like each student is practicing alone.

We walk down another flight of stairs and enter a hallway identical to the one above us. There are more closed and numbered doors, more ear-rending rehearsing. My accomplice mentions that there's been complaints from individuals in her office regarding the unbearable noise emanating from 1120 Bolyston. (This is from an online review I unearthed regarding the address. It seems to indicate that aside from serving as practice space, permanent residency is permitted as well: "Living here for few months was one of the worst decisions I've ever made in Boston! ... In the building, this is where the Berklee students live so you can constantly hear someone playing their guitar/contra-base/saxophone. If you're looking to live in a peaceful and quiet neighborhood, this is THE WORST place.")

We pass a grimy, communal bathroom. Mouse shit is piled in corners; down one dead-end hallway we find an expired rat stiffening in a trap. The hallways are gloomy—not enough to make walking precarious, but enough to generate an atmosphere of slight unease. The air smells of dirt and decay and sour sweat. Our steps stir papers stuck to walls—flyers with tear-off tabs advertising the services of amp repairmen and experienced upright bassists. People occasionally pass us in the halls, but for the most part, the only sign of human life is the instruments playing. A location so maze-like prompts me to joke about the need for a breadcrumb trail to find our way out. I mention my visit to the catacombs underneath Paris and how worthy parallels could be drawn between there and 1120 Bolyston.

Back on the street, we blink our eyes as they adjust to the afternoon light, breathe in the autumn air. My accomplice and I speculate on what live shows in such a squalid setting were like. Today's area venues are pristine, sterilized. The journey into Boston's old Catacombs club leaves me fully admiring Van Morrison's strength of vision. Astral Weeks' gestation took place in a shadowy cavity hollowed out of the dank earth beneath urban streets. Yet such murky origins never altered Morrison's belief that these songs were spirited, vibrant, sweeping reflections of his gold-rimmed adolescence. Hell never touched his heaven.

Monday, November 4, 2013

Truly deserving of the name 'the Catacombs'

So I'm sorting through the bits of conflicting information I have received regarding the whereabouts of the Catacombs. Bear with me here ... When I met with Liz Lupton, publicist from Berklee College of Music, I had the honor of getting a full tour of her office, which is located on the second floor at 1126 Bolyston Street.

During my visit, Lupton, as well as a co-worker of hers with extensive knowledge of the Boston music scene, said they were quite confident their office space was the former site of the club. When Lupton and fellow Berklee employees moved into the location roughly a year ago, they were informed that a well-known live music club was once situated in the office space directly above 1120 Bolyston (a piece of information, according to Lupton, that absolutely thrilled the musicophiles in her office).

When Lupton saw my email about the Catacombs and 1120 Bolyston, she naturally concluded that the venue I was inquiring about was the one formerly located at her workplace. However, after leaving her office, slinking through the street-level door that sits at 1120 Bolyston, and exploring the spaces one and two stories below, Lupton felt differently regarding the Catacombs' true location. And I couldn't help but agree with her. The subterranean expanse beneath 1120 Bolyston, with its labyrinthine hallways, musty darkness, and slight air of secrecy, was truly deserving of the name "the Catacombs."

Here is further proof that this underground setting was where the club resided: This is information I received from Doug Ferriman, founder and CEO of Crazy Dough's Pizza, which has a location at 1124 Bolyston St.:

Its funny you ask about the catacombs. I tell stories about that place all the time! Long story short, the space was handed down from band to band over the decades (the last band being close customers of mine) and served as an underground musician/band hangout/jam venue. It was very cool down there, old stage, an old bowling alley way back when it was a jazz joint ... The space has been broken out into multiple rehearsal studios for Berklee and Conservatory kids. I don't think there is any characteristics left of the old hang out. It is owned and operated by the Hamilton Company ... I believe I am one of the last people down there before it was gutted. My memento was an old steel drum I always eyed on the wall, so it was nice when the guys gave it to me.

Tuesday, October 29, 2013

Wiping our feet

Liz Lupton, a publicist at Berklee College of Music, wipes her feet on the sidewalk, a gesture akin to someone vigorously wiping their shoes on a doormat following a long walk through heavy mud. We breathe in the late autumn air, squint as our eyes adjust to the afternoon daylight. "I went to college in Indiana and lived with four girls," Lupton tells me, "and our place wasn't nearly as gross."

Lupton and I are standing outside 1120 Bolyston Street in downtown Boston. The busy block is part of Berklee's sprawling urban campus; students dart past alone or in groups, carrying unwieldy instrument cases and oversized knapsacks. Had I the need to form a competent backing band, a 30-second canvassing of my immediate area would have unearthed all the necessary musicians (I may have even saw a flugelhorn). My thoughts suddenly turn to Van Morrison and how he just did that—right here, at Berklee, one of the world's most prestigious music schools. And how night after night for months, a pair of young music students followed him through the battered door behind me, down a long set of stairs and onto a tiny stage, where they performed to crowds of varying degrees of size and enthusiasm.

I'm standing outside 1120 Bolyston Street, site of an old music club known as the Catacombs. If the place where Astral Weeks' heart began beating was Morrison's cramped bedroom in Belfast, then it was here at the Catacombs that the album took its first sharp breaths.

More to come ...

Friday, October 25, 2013

Mouse-shit-filled hallways

So I ambled through (what I believe was once) The Catacombs. One, two stories below 1120 Bolyston St. I explored mouse-shit-filled hallways. Passed through rank, darkened spaces; crept down steep, deserted stairwells. Came up for air, rubbed my eyes on a coat sleeve.

I will eventually post more about my adventure. Still sorting out the conflicting and interesting information I have received regarding The Catacombs and its whereabouts. But I have to say: The place I visited certainly felt like it. There, the living sang unaccompanied and the dead harmonized.

Tuesday, October 22, 2013

"A lot of allegory"

Elliott Smith died 10 years ago yesterday. I mention this on a blog dedicated to Astral Weeks because of a passage I read in Pitchfork's oral history of Smith's music:

DORIEN GARRY: But it would infuriate him when people asked him what his lyrics were about. He really hated having to have an answer for what every character and every story was. Music was a way of channeling thoughts and feelings that were bigger than him into art, and he didn't feel like he owed every single person an explanation of what everything was about. LARRY CRANE: His lyrics are parables and observations. The biggest mistake people make is assuming his songs are all confessional. It's his own life, but it's a lot of allegory. You see recurring characters in his songs.This ran parallel to an excerpt from Clinton Heylin's biography of Van Morrison, Can You Feel the Silence?, which analyzed the Irishman's approach to songwriting:

Morrison has always fiercely resisted autobiographical interpretations of his songs, often in the face of indubitable evidence ... And yet it seems quite inconceivable that such a young, inexperienced writer could construct such an internally consistent universe, and place at its centre a girl perfectly suited to her surroundings, save from personal experience.Along with Astral Weeks, Smith's self-titled release is among my favorite 20 or so albums of all time.

Friday, October 18, 2013

An autumn impression (featuring beer)

On Saturday, I sat lazily atop a picnic table, drinking beer from a can, relishing how the White Mountains' autumn days—no matter how cloudy or cloudless—always feel so pleasantly low-lit, like when you turn down the dimmer switch in a room. Happily seduced by one of those "lonely intervals where the afternoon lingered" (so described by Henry James in his essay "New England: An Autumn Impression"), I watched the leaves lightly fall from a small maple tree. There was no soft breeze, no animal darting along a branch, no fat raindrops; each leaf's pleasing departure and descent was not the consequence of another event. They fell simply because it was time to fall. It was all so cosmically pure and epic. I opened another beer.

I thought of Astral Weeks and wondered if when the album was recorded—three fall days in 1968: Sept. 25, and Oct. 1 and 15—had any influence on its mood and tone. Autumns in my foliage-bedecked corner of the world are dominated by flashes of warmth and pangs of loneliness. It's like walking back and forth between one room with a fire on the hearth and another without. Exploring the Jackson/North Conway area's diabolically twisted back roads, I saw a man whose skin was flushed red from physical exertion and at his feet were brown, crumbled husks and they were trampled into the cold, acrid earth and I thought, Okay, so that's autumn.

In the fall, you feel quite alive among the death and decay. This contrasting state of affairs spurs reflection on where you are, where you've been, and where you are going. You are strengthened by the future, weakened by the past, tormented by the last vestiges of color, emboldened by a promise of rebirth. You are enchanted by the cold steel of a vacant railroad bridge, an empty swimming hole, a forlorn-looking skiff for sale on a yellowed lawn, a deserted diner advertising homemade pumpkin bread, a lone church steeple set against a vibrant backdrop, cold rain pelting an air conditioner left in a window. Do we hear any of that in Astral Weeks? Possibly just a little bit? Maybe?

Wednesday, October 16, 2013

Thursday, October 10, 2013

A diagnosis and a prescription

Here's a story from well-known music critic Steve Hyden. The gist is rather straightforward: Hyden submits suggestions to artists regarding what directions they should go on their next releases. Writes Hyden: "I picked these artists because (for a variety of reasons) they seem like they could use a little album-doctoring."

In case you're all clicked-out right now, I will post one of Hyden's prescriptions. This one is intended for Madonna, who recently mentioned the possibility of a new album in 2014. (Quick and boring aside: Hyden's prescription for Madonna was the one I found myself agreeing with the most, primarily because I've willingly dismissed her oeuvre with the exception of ballads such as "Live to Tell" and "Oh Father"—ballads that conflate sentimentality with slickness so effortlessly I found them poignant at age 14, schlocky at 24, and then crushingly poignant at 34.)

The diagnosis: The last 30 years of pop music would look and sound very different were it not for Madonna—on this point we can all agree. What's debatable is what exactly people want from a Madonna record now that she's in her mid-fifties. Do we want Madonna to make 12 songs that re-create the sound of "Lucky Star" and "Into the Groove?" Or do we want her to work with hip producers in order to "reinvent" herself? The prescription: Actually, I'd like to see Madonna avoid dance music altogether. Instead, I think she should spotlight her ballad-singer side. Madonna's slow songs are typically undervalued, but I think they rank among her best: "Crazy for You," "Live to Tell," "Oh Father," "Rain," "Take a Bow," "Frozen," and so on. I'd love to see her make a dark, borderline goth record reflecting the unique perspective of a pop diva several decades deep into the game. (Sort of like a Bat for Lashes record meets Dylan's Time Out of Mind.) She can always follow it up with a greatest-hits tour, but this kind of album would be unique in her catalogue and potentially stand out as one of her most intense and rewarding.Feeling beaten and uninspired, I whipped up a prescription and diagnosis for Van Morrison—one that would have been penned by 1969's answer to Hyden and came on the heels of the tepidly received Astral Weeks. The diagnosis: A half-decade into his career and already Van Morrison has become a frontman of startling ferocity. Belfast blues, ginger-haired soul, three-cord power anthems—whatever type of canvas Morrison is painting upon, he invariably does so with brute power and sharp clarity. However, Astral Weeks felt like a misstep, a meandering and bloated heap of self-indulgence. With his mentor, Bert Berns, cold in the ground and a new label, Warner Bros., eager to please their Irish wunderkind, the 23-year-old Morrison was left to his own devices. He ultimately strove for epic and ended up sounding overwrought. The prescription: Astral Weeks' lone strength was its effusive appreciation for a particular time and place: Morrison's adolescence in Belfast. In a way, he was returning to his roots. Morrison's next album should do much of the same—only this time, go a bit further back, all the way to his prepubescent years. What if Morrison stepped out from behind the cluster of notable jazz musicians that sheltered him on Astral Weeks, shelved his notable gruff persona, and tackled the airy and lighthearted folk songs many of his contemporaries (including some of the Irish variety) are covering? How wonderful would it be to hear Morrison inject his trademark uncurbed exuberance into kiddy ditties like "Wynken, Blynken, and Nod," "The Unicorn," and "The Marvelous Toy?" After the debacle that was Astral Weeks, such a youthful shift in direction would be rewarding to both Morrison and his fans.

Monday, October 7, 2013

Distant music

From James Joyce's "The Dead":

Gabriel had not gone to the door with the others. He was in a dark part of the hall gazing up the staircase. A woman was standing near the top of the first flight, in the shadow also. He could not see her face but he could see the terracotta and salmon-pink panels of her skirt which the shadow made appear black and white. It was his wife. She was leaning on the banisters, listening to something. Gabriel was surprised at her stillness and strained his ear to listen also. But he could hear little save the noise of laughter and dispute on the front steps, a few chords struck on the piano and a few notes of a man's voice singing.Gretta, we're informed, was listening to "The Lass of Aughrim." Saturday morning, as the strains of "Beside You" played softly in my subconscious, gleefully trapped in my bed, a book balanced on my chest, I pretended rather foolishly that Gretta was paralyzed by Astral Weeks.

He stood still in the gloom of the hall, trying to catch the air that the voice was singing and gazing up at his wife. There was grace and mystery in her attitude as if she were a symbol of something. He asked himself what is a woman standing on the stairs in the shadow, listening to distant music, a symbol of. If he were a painter he would paint her in that attitude. Her blue felt hat would show off the bronze of her hair against the darkness and the dark panels of her skirt would show off the light ones. Distant Music he would call the picture if he were a painter.

Wednesday, October 2, 2013

Personal dispatch #8

This is a dispatch from Ferdia Dwane, who recorded a pair of crisp, clean covers of Astral Weeks tracks. Dwane's voice splendidly strains to reach the upper registers; his guitar strumming is brisk and expressive, yet always controlled. He provided a bit of background information, as well as why he performed these particular songs.

I am from Cork in Ireland, 21 years old. I've been playing music since I was a child. I don't perform very frequently in a public setting (outside of family occasions), but I plan on performing more over the next year. I am a huge fan of Astral Weeks; out of the many records I own I would consider it my favourite. Honestly, the reason I chose those two songs to cover was just a matter of wanting to cover songs off Astral Weeks and realising those two were probably the most straightforward to learn. I generally record all my music in my house, mostly in my bedroom using a Zoom H2 microphone and GarageBand. Recording takes anywhere from 20 minutes to an hour. But with these tracks they were thrown down pretty quick.

Sunday, September 29, 2013

Muted lamp light

Just as there's something warm and wonderful about listening to vinyl in the shadowy isolation of your bedroom, so too is there something generously pleasurable about recording a cover song on your own turf. Muted lamp light, a tightly closed door, a large, empty water bottle looking forlorn on a dresser. Refraining from shifting on the bed that way the box spring's creaks and groans don't find their way onto the recording. Keeping your vocals hushed and your strumming softened so as not to wake those who are slumbering. Feeling relief when the cover is finished because you've gotten out everything you had bubbling inside you.

Thursday, September 26, 2013

Cross-generational allure

Author Greil Marcus, one of Astral Weeks' most distinguished and ardent supporters, once discussed the album's power to transcend its era. While teaching at Princeton University, Marcus handed out questionnaires, asking his class to list their favorite books, movies, and albums. Of his 15 students, four selected Astral Weeks.

From a 2010 interview with Marcus regarding his book, When That Rough God Goes Riding: Listening to Van Morrison: "Now these are people who were born in the late eighties, twenty years after the album had been released. It's conceivable their parents weren't even born when the album was released. And yet this album had found them, or they found their way to it."

Of course, Marcus' evidence of Astral Weeks' cross-generational allure is purely anecdotal. However, it's not too far-fetched to contend that a particular subset of today's teenagers and 20-somethings are devotees to the album, simply because the Internet has allowed music listeners, adolescent and aged, to enormously expand their palettes and become easier acquainted with artists from formerly out-of-reach time periods, genres, cultures, and so forth.

What I'm curious about is how young audiences initially react to Astral Weeks or more specifically, what they think about the sheer density of its content. During my first listening experiences I found the album to be near impenetrable, both sonically and lyrically (gee whiz, more anecdotal evidence?). Astral Weeks was a tightly-guarded fortress; no matter how many times I assailed its walls, I could never reach its heart. Growing up, my exposure to Van Morrison was restricted to my parents' playlists, which leaned heavily on radio staples, Into the Music, and scattered offerings from his '90s oeuvre. I couldn't believe Morrison was capable of such startling—yet mildly bewildering—complexity.

So what do young audiences think? I pose this question because of what I've been told regarding the behavior of Millennials—those individuals born between (give or take a few years) 1980 and 2000. "Connected" does not begin to describe their life experiences; "hyper-connected" is more apt. They are early adopters of new technologies and passionate users of texting, emailing, and social networking. They are characterized as having short attention spans, relentless preoccupations with multi-tasking, and exhaustive appetites for information. One story I read humorously diagnosed Millennials with AOADD: Always-On Attention Deficit Disorder.

Wall Street Journal critic Terry Teachout wrote about how modern theater would benefit from a more improved effort to win and sustain audience attention: "The leisurely expositions of yesteryear, it turns out, aren't necessary: You can count on contemporary audiences to get the point and see where you're headed, and they don't want to wait around for you to catch up with them." Could the same be written about music that's uncompromising and challenging? About Morrison and his nearly 10-minute long opus "Madame George"—or Astral Weeks' three other tracks that clock in at over seven minutes long?

Of course, this is all unfair. Characterizing an entire generation is eternally misguided. One also can't presume that Millennials approach art in much the same way they approach Facebook news feeds, posts on Tumblr, or Google search results. The Internet may have slightly eroded our ability to remain focused, but I like to believe it hasn't spoiled our appreciation for art, particularly that which tests our patience and stamina. Because ultimately, the payoff from such art brings the most satisfaction.

From a 2010 interview with Marcus regarding his book, When That Rough God Goes Riding: Listening to Van Morrison: "Now these are people who were born in the late eighties, twenty years after the album had been released. It's conceivable their parents weren't even born when the album was released. And yet this album had found them, or they found their way to it."

Of course, Marcus' evidence of Astral Weeks' cross-generational allure is purely anecdotal. However, it's not too far-fetched to contend that a particular subset of today's teenagers and 20-somethings are devotees to the album, simply because the Internet has allowed music listeners, adolescent and aged, to enormously expand their palettes and become easier acquainted with artists from formerly out-of-reach time periods, genres, cultures, and so forth.

What I'm curious about is how young audiences initially react to Astral Weeks or more specifically, what they think about the sheer density of its content. During my first listening experiences I found the album to be near impenetrable, both sonically and lyrically (gee whiz, more anecdotal evidence?). Astral Weeks was a tightly-guarded fortress; no matter how many times I assailed its walls, I could never reach its heart. Growing up, my exposure to Van Morrison was restricted to my parents' playlists, which leaned heavily on radio staples, Into the Music, and scattered offerings from his '90s oeuvre. I couldn't believe Morrison was capable of such startling—yet mildly bewildering—complexity.

So what do young audiences think? I pose this question because of what I've been told regarding the behavior of Millennials—those individuals born between (give or take a few years) 1980 and 2000. "Connected" does not begin to describe their life experiences; "hyper-connected" is more apt. They are early adopters of new technologies and passionate users of texting, emailing, and social networking. They are characterized as having short attention spans, relentless preoccupations with multi-tasking, and exhaustive appetites for information. One story I read humorously diagnosed Millennials with AOADD: Always-On Attention Deficit Disorder.

Wall Street Journal critic Terry Teachout wrote about how modern theater would benefit from a more improved effort to win and sustain audience attention: "The leisurely expositions of yesteryear, it turns out, aren't necessary: You can count on contemporary audiences to get the point and see where you're headed, and they don't want to wait around for you to catch up with them." Could the same be written about music that's uncompromising and challenging? About Morrison and his nearly 10-minute long opus "Madame George"—or Astral Weeks' three other tracks that clock in at over seven minutes long?

Of course, this is all unfair. Characterizing an entire generation is eternally misguided. One also can't presume that Millennials approach art in much the same way they approach Facebook news feeds, posts on Tumblr, or Google search results. The Internet may have slightly eroded our ability to remain focused, but I like to believe it hasn't spoiled our appreciation for art, particularly that which tests our patience and stamina. Because ultimately, the payoff from such art brings the most satisfaction.

Monday, September 23, 2013

Instrumental cuts

Wu-Tang Clan and Van Morrison ... Where can we draw parallels? Well, both are deeply indebted to a specific place: For Wu-Tang, it's Shaolin/Staten Island; for Morrison, Belfast. Unearthing further correlations would mean citing falsehoods and misrepresentations and other assorted bullshit. Let's not do that. Instead, let's click on the above link. It features instrumental cuts of the best tracks from Liquid Swords. With the vocals pared away, the listener is allowed to fully appreciate the album's toxic beats. Your ears will ripple and shudder with orgasm.

I wish some industrious YouTuber would do the same with Astral Weeks. I'm aware that such a request is borderline blasphemous. Morrison's vocal performance is nothing short of transcendent; he "plays" his voice as masterfully as any of Astral Weeks' session musicians play their instruments.

But at the same time, how else could we wholly cherish: the swelling strings on "Sweet Thing" and how they melt into the heartbeat of Richard Davis' double bass; the sprightly harpsichord in "Cyprus Avenue" or how in the same track, Davis' bass lines gloriously enliven empty spaces; the wistful sound of Morrison strumming the G, C, and D chords to open "Madame George; the hiss of Connie Kay's hi-hat and the humming dirge of the cellos in the same track; or the shivering, itinerant soprano saxophone in "Slim Slow Slider."

Wednesday, September 18, 2013

Baa, baa, black sheep

A decade ago, music writers began penning obituaries for the traditional album cover, citing its relegation to postage-stamp dimensions on mp3 players or its frequent total absence when a release was downloaded illicitly. This was the terminus for a gradually shrinking medium—the end point for a reduction that commenced when vinyl waned in popularity, and the 12-inch-by-12-inch canvases once used by artists and record companies gave way to the centimeters worth of tiny space offered by cassettes and compact discs. Album art, we were informed, was poised to become less creative, less conspicuous, more utilitarian, a mere label for the music product it was packaging.

These requiems were a bit premature. Vinyl staged a bit of a rally. Meanwhile, music became instantaneous and ubiquitous, the sheer amount of musicians yearning to be heard seemingly infinite. And that means photography, typography, and graphics that are eye-catching to consumers—even when using that significantly miniaturized canvas—can still rank as crucial components of an release's success.

What does the album cover's small revival in importance mean for Astral Weeks? Primarily this: Its rather second-rate artwork will continue to perpetuate the myth that Van Morrison functions as some sort of hippie troubadour, that the music of Astral Weeks is the ideal soundtrack to druggy experimentalism and cliched attempts at transcendence. It's a myth that's existed since the album's release 45 years ago. From Steve Turner's Too Late to Stop Now:

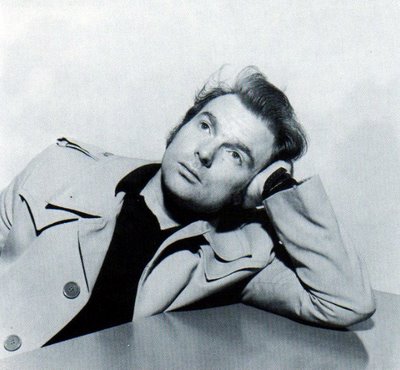

For many people at the time Astral Weeks perfectly articulated the experience of the acid trip, with its invocation to be born again and its subsequent journey through layers of childhood experience in flashback sequences. It became one of the essential albums for travelers on the "hippie trail" from Europe through to Kathmandu, and there were even reports of vans painted in psychedelic colours being renamed "the Van Morrison."If you're reading this blog, you're certainly familiar with the album's cover, and the hallucinatory and gauzy—yet at the same time, hackneyed—vibe it emits. The photo, as well as the absurd poem printed on the insert, was intended to compliment the album's themes of otherworldliness, nostalgia, youthful passion, devotion to place, etc. Instead, the art feels embarrassingly unimaginative, slightly anachronistic, even off-putting (all that green and black; ick)—essentially everything that is the antithesis of Astral Weeks. When Morrison's lifted-from-an-adolescent-diary poetry isn't eliciting a giggle ("When I got back it was like a dream come true"), it has you scouring the Internet for lewd jokes ("Loved you there and then, and now like a sheep"). In the photo, a disoriented-looking Morrison stares downward, possibly at his hands or his shoes or his acoustic guitar (or a sheep). And have I mentioned the green-and-black color scheme? Warner Bros. did have good intentions when it was developing the album's artwork. The photograph was snapped by Joel Brodsky, a notable New York photographer credited with shooting the hard-to-imagine total of 400 album covers. Interestingly, Brodsky photographed a number of moderately successful bluesmen—Buddy Guy, Otis Spann, John Lee Hooker, and Junior Wells, to name a few—a fact that would have certainly thrilled the blues-obsessed Morrison. His more well-known clientele included Joan Baez, Kiss, the Stooges, and the MC5. And oh yes, he also did this photograph, a staple of any white male college student's dorm room. There is certainly worse album art in the Morrison discography. And when one considers the packaging of other iconic albums from the late '60s, Astral Weeks' faults don't appear so egregious. There's also this: The release's eight tracks transcend its packaging. As avid listeners can attest, spend a bit of quality time with Astral Weeks and you eventually recognize that the hippie troubadour/experimentalism/drug motifs cited above are misguided at best, disingenuous at worst.

Monday, September 16, 2013

Shaking the stalagmites from my tongue

We chat about music, but I typically do most of the chatting. Fueled by great tumblers of drink, which shake the stalagmites from my tongue, and a passion that goes from smolder to blaze when I'm in the presence of others similarly devoted to consecrated acts of music consumption, my words are, simply and unabashedly, endless. One night you spluttered, and my first thought was this was the act of a man drowning in talk, a man coming up for a breath of air, desperate to be rescued by the very individual who was drowning him. Only you had tipped your glass back for a drink and the liquid funneled down the incorrect pipe. I delivered several sharp blows to your back—and then continued chatting.

One summer, in the dimly-lit and dust-touched sitting room of a faraway vacation home, I prattled on about Jason Pierce and how his songwriting veers toward the embarrassingly honest and how frequently his candidness includes drug-related confessions that are blunt and rhapsodic, and as I classified them as "art" and "artful" and "art created by an individual sacrificing himself for art" I couldn't help but wince, because they also feel like a cluttered, detached addict merely wishing to celebrate his gutter-worthy position as a cluttered, detached addict. Your confidence in my mental health was shaken a little; I could tell, even if you didn't vocalize it. But really, how much joy can truly be derived from a passion—even if that passion is druggy songwriters—when it's sealed away inside you?

I'm not always playing the role of incessant talker; occasionally I am a vigilant listener. There was a night where a large party was whittled down to just the two of us. We sat on the couch with drinks, playing deejay on iTunes, the clock on the wall making slow progress toward some ungodly hour. I clicked on "Ballerina" and you talked. The standing-in-the-doorway moment—you loved that. Van Morrison perched on a threshold, a lifetime of decisions bringing him to this very specific moment, a decision of a lifetime waiting to be made. "He's smitten," you kept declaring. "Smitten."

We said the word over and over until it no longer even sounded like the word—or any word, for that matter. It was just a sound, all soft s's and crisp t's. Maybe we were subconsciously taking a cue from Van Morrison. Maybe incantations of the word permitted us to fully grasp and appreciate "Ballerina"'s climax. Maybe we were drunk.

In any case, I suddenly felt like a transaction took place between us, in which you and myself and Astral Weeks were now on one side, and life was on the other, and that side was always trying to get the better of us, and occasionally we rumbled toward a confrontation, but without fail and without losing too much skin, we held off every advance.

Wednesday, September 11, 2013

Personal dispatch #7

This is a dispatch from Marty Rod, who recorded a smoldering, gauzy, reverb-drenched rendition of "The Way Young Lovers Do." His cover is like watching a cigarette slowly burn a crisp, black hole in a bolt of silk. Rod told us a little about himself, as well as why he selected this particular track from Astral Weeks.

I was born and raised in Reseda (popularized by Tom Petty and The Karate Kid), which is in Los Angeles suburbia. I'm 26 years old and have been a professional musician, at least in terms of making a living off music, for the past two years. I started singing before I could remember. I started playing guitar at 12 and was writing songs by 16. I think that in today's music industry being multi-dimensional is a necessity to staying active and establishing a career. To that end, I started learning multiple instruments and consuming knowledge on production and recording ever since I was in college. Now I often record and mix many of my own songs. I've done numerous productions for other artists as well as TV shows and films. I perform with my band and my pet project, Bravesoul, mostly here in the Los Angeles area. I also do acoustic performances in Venice at the Wizend one to two times a month. I've always been a huge fan of Van Morrison. I was a bit older when I first heard some of the songs off Astral Weeks—most likely in college at some point—and I must admit, I didn't really "get it" at first. I think I had heard "Sweet Thing" and "Madame George" on a road trip and thought they were cool songs, but I didn't really connect with them. I think growing up in a generation that's entirely focused on mp3s and singles, it took me a long time before I realized the difference between a compilation of songs and a true album. Astral Weeks is definitely a true album and it was an eye-opening lesson in that respect. It's something that should be heard in its entirety. Only then can you really enjoy the improvisational and fluid arrangements, and the pure childlike emotions that seem to grow stronger from song to song. It's more of an experience that needs to brew and be felt, rather than a three-minute espresso shot of energy and catchy hooks. "The Way Young Lovers Do" was one of those songs I heard while listening to the full album. The lyrics immediately moved me. It's not an uncommon theme by any means, but I loved the delicate and innocent way he painted the scene. It was so simple and direct, and the song seems to transport you to a different time and space. It also seems to stand out from the rest of the album both in its simplicity and its more traditional form and structure. In hindsight, that no doubt may have also been one of the reasons I initially gravitated towards that song. I wanted to cover the song for the same reason i think you should cover any song: I thought I could do it a bit differently. Songwriters like Van Morrison or Bob Dylan are always great fodder for covers because they have very distinctive voices/styles and their songwriting is amazing. In other words, it's not hard to sound different. And the lyrics and melody give you a powerful foundation to pretty much take the song in many directions. In my mind, I wanted to take the song more into the spaghetti western world and make it more of a full-on cinematic experience. I decided to make it a duet for that same reason as well. I recorded everything in my living room here in west L.A. I brought my good friend and writing partner Jacqueline Becker on board to lend her beautiful voice and make it a duet. The recording and mixing process literally took no more than a single day. It just took a stroke of inspiration and within about eight hours it was all done.

Friday, September 6, 2013

A meticulously considered approach, aesthetic, and atmosphere

Mike Powell, who is one of my favorite music critics born during the compact disc era, recently launched a column named "Secondhands" for the popular music site Pitchfork. It examines, according to the introduction on the first "Secondhands" entry, "music of the past through a modern lens." Okay, so as far as mission statements go, that one's rather terse and ambiguous. When it comes to substance, however, Powell is anything but.

The latest "Secondhands" piece covers Astral Weeks. Aside from an occasional bout of hyperbole ("Nobody who played on the sessions for Astral Weeks has anything nice to say about the experience") and a closing paragraph that feels tacked-on, the piece deftly illustrates why the album resonates with a particular subset of listeners (including Powell).

... The artist as someone who is not well-rounded, who is not capable of seeing all points of view or transcending the confines of their own perspective—basically, the myth of the artist as someone who has yet to transform from a child into an adult.Then there's this:

Audiences can appreciate this myth because they've probably experienced flashes of romantic single-mindedness, too. But it's also that life—in its variety and responsibilities—doesn't give us much room to be single-minded, and so we need to step sideways into the parallel universe of art, where we're allowed to feel those narrow teenage feelings for as long as the album lasts.Powell's reference to a particular single-mindedness hints at what I feel is one of the principal reasons Astral Weeks is so extraordinary: There was a fascinating dichotomy at work during the album's three sessions. Even though lyrics flowed stream-of-conscious-like and the assembled musicians were instructed to play "whatever they felt like playing" (per drummer Connie Kay), Morrison was strictly devoted to a meticulously considered approach, aesthetic, and atmosphere. Astral Weeks is metamorphic, fluid, and loose—all because months of refining the material at his parents' home in Belfast and the Catacombs in Boston gave him a rather rigid and precise vision of how the album should sound. Astral Weeks is formless by virtue of its stringent form. (In typical Van Morrison fashion, the singer-songwriter later claimed that the finished Astral Weeks product didn't quite meet his expectations. "I didn't really get into it as much as I thought I would," he claimed. Also: "I was kind of restricted, because it wasn't really understood what I really wanted.")

Wednesday, September 4, 2013

Frayed memories / memories are frayed

Still scouring the Internet for information on the Catacombs, the Boston club where Astral Weeks took its first sharp breaths, where Van Morrison collaborated with a pair of Berklee College of Music students—upright bassist Tom Kielbania and flautist/saxophonist John Payne—before New York City and Century Sound Studios beckoned.

Harry Sandler, co-founder of the Music Museum of New England and one-time drummer for the band Orpheus, provided me with a bit of background. Carl Tortola, webmaster for the museum, recommended I get in touch with Joe Viglione, who was involved with the Boston music scene in the '60s and '70s. Joe linked me to a gig poster for the J. Geils Blues Band. The group performed at the Catacombs during January of 1968 (Morrison and company played that summer). However, Joe had little else to offer other than names. One was Rick Harte, who responded to my query with this:

Hi, Ryan. I remember going there. It was down several flights of stairs. I didn't go there much. But it's true: Van Morrison lived in Cambridge for a long time. On Green Street, Kirkland, or Kneeland. I'm a huge fan of Them and the early Van Morrison solo years. While I was around then and would see him, it's still way over 40 years ago and memories are frayed.Another contact, Jason Brabazon, was also contending with frayed memories:

It's funny (peculiar), a lot of times, even tho' I'm sure I remember where something (in Boston; music-related or otherwise) used to be, it turns out my memory has failed me. I was certain I remembered where the entrance to Paul's Mall & the Jazz Workshop was, but when I found an old ad showing the Boylston St. address, I was way off! I think (in retrospect) that I was in fact remembering where the Unicorn Coffee House used to be. When I was a kid (single digits), my mum and her friends used to talk about this sort of thing (like where Scollay Square used to be or such-and-such a restaurant before they tore it down) and I remember thinking: I'm glad I'm not so old that my world has evaporated around me. But now, here we are ... I'm sorry I can't be of more help. I was around when he lived here (Green Street), but it's not like we hung out or anything. I remember him playing a free concert on Boston Common and singing "Rain, rain, go away." I think to the tune of "Ro Ro Rosey." I may still have the flyer somewhere. It was billed as the "Van Morrison Project" or something like that. At first I wasn't even sure it was really the actual guy. I thought it must just be the name of some band; like if you saw a billing for a band called the Bela Lugosi Initiative, you wouldn't expect it to actually be the Bela Lugosi. And what would someone as big and famous as Van Morrison be doing playing for free?So I soldier on ...

Friday, August 30, 2013

Painstakingly remade

This is Astral Weeks modernized. Fitting, I suppose, because over the past 15 years Belfast has been painstakingly remade. Murals become a primer coat for compositions less incendiary. Hulking, glistening, tapering edifices are constructed of silver-anodized aluminium shards.

StraightFace's cover of "Astral Weeks" is equally novel and synthetic. It's a track with an electronic bent; sequenced notes emulate notes that once emerged from human bellies. It firmly grasps the soul of Van Morrison's original song and gently places it inside a chest fashioned from sparkling plastic.

Thursday, August 29, 2013

Roadkill

This is one of my recent favorite exchanges on the subject of Astral Weeks' merit and worth. It was snipped from PopMatters' ongoing Counterbalance series, which features writers Eric Klinger and Jason Mendelsohn deconstructing and vivisecting music's quote/unquote great albums. Essentially, it's the music-crit equivalent of two men shattering a deer with their car and then getting out and fingering the viscera, and tossing around astute and witty observations regarding the consistency, blush, and fragrance of the guts.

Mendelsohn: I'm not saying it doesn't deserve the accolades, but Astral Weeks (and I feel a bit silly saying this) may be the least accessible record we've talked about thus far ... Astral Weeks is a rambling record with a heavy jazz influence, lyrics that rival beat poets, and the average track goes on for seven minutes. It's no wonder no one cared when it came out.

Klinger: See, now this is one of those times where you and I can say the exact same sentence and mean the exact opposite. After all, Astral Weeks is a rambling record with a heavy jazz influence, lyrics that rival beat poets—and the average track goes on for seven minutes! What's not to love?

Tuesday, August 20, 2013

Graffiti

On a brick wall along my own private Cyprus Avenue—a Cyprus Avenue I hold deep inside, a Cyprus Avenue that's encircled, swathed, and gently paved over my soul—there are words written in a fine and flowing hand, words penned with paint made from charcoal, children's spit, and animal fat. They lie beneath the shade of Austrian pine and common lime: "I wonder if it seems to you / Luriana Lurillee / That all the lives we ever lived / And all the lives to be / Are full of trees and waving leaves." This is from "A Garden Song," a poem by 19th century English politician Charles Isaac Elton. They're Astral Weeks-like in both essence and substance, no?

Saturday, August 17, 2013

Personal dispatch #6

This is a dispatch from Modal Roberts, who cut a rather spastic and unnerving rendition of "Astral Weeks." Dubbed "Astral Weeks Suicide" (and recorded under the pseudonym Johns Original Wife), it's unlike any Van Morrison cover I have heard. It transforms a gorgeous paean to rebirth into a ferociously deranged assault on your soft, white soul; it's music to be damned to. It's like a long, steaming piss on a bed of dahlias. It's No Wave having a thumb war with Celtic soul. Roberts provided a little background on the recording of the song.

I like the whole of Astral Weeks not just the one song and would like to cover more tracks from it. [This] is an improvisation with me doing vocals and a friend doing keyboard. The idea was to do the song in the style of New York electronic duo Suicide. I am a big fan of theirs, too. It seemed like fun to take Astral Weeks from its pastoral, acoustic setting and transplant it into an alien, urban, electro environment, while still keeping its poetry intact. It was just something we did to amuse ourselves and I haven't listened to it for ages. But listening now, I think it sounds pretty good. I like the energy and the impro around the lyrics—pulling in a bit of Moondance even!

Wednesday, August 14, 2013

"Meagerly Yeatsian"

The adjective "Yeatsian" incessantly nips at Van Morrison's heels. Where the blame lies is not so much Morrison's verses and choruses, but persistent talking points. For every verse he committed to exploring themes even casually associated with mysticism, he devoted three interviews to prattling on about the creative, otherworldly impulses behind such lyrics.

Critics, biographers, and fans have seemingly identified instances of mysticism in just about every deep fold and shallow crevice in the Morrison catalogue. W.B. Yeats and the singer/songwriter are frequently and enthusiastically cited as two peas in an ethereal pod. The opening of Steve Turner's book Too Late to Stop Now features a full-page photograph of Morrison sitting pensively among sunset-colored drop cloths and lagoon-colored drop cloths, complete with a Yeats quote for the caption: "Above all, it is necessary that the lyric poet's life be known, that we should understand that his poetry is no rootless flower but the speech of a man."

The reality is Morrison's indebtedness to Yeats is overblown at best, disingenuous at worst. "Marginally Yeatsian" is a more promising description or "meagerly Yeatsian" or even "Yeatsian to such a tiny degree it's hardly worth discussing with friends over pints or with strangers at bus stops." Morrison's writing style is beholden to no single influence other than his own quote/unquote cleverness. It's why the task of penning lyrics often finds him guilty of committing the most unconscionable artistic sins. From biographer Johnny Rogan: "Meaningless repetition, poorly thought-out imagery, cloying sentimentality, cosmic buffoonery, faux and gratuitous literary name-dropping, heavy-handed symbolism or decorative words employed purely for their poetic association are all there in embarrassing abundance."

Morrison's true intersections with Yeats: his "Before the World Was Made" appeared on 1997's Now and in Time to Be: A Musical Celebration of the Works Of W.B. Yeats; also, his intent was to record a musical adaptation of the poem "Crazy Jane on God" for 1985's A Sense of Wonder, but he was denied permission by Yeats' executors, which prompted a sullen Morrison to respond, "I thought I was doing them a favor—my songs are better than Yeats."

Nonetheless, despite spending several hundred words poking holes in any Morrison-Yeats parallels, there are three Yeats lines that have long reminded me of Morrison and his Belfast home:

"Out-worn heart, in a time out-worn / Come clear of the nets of wrong and right"

"But I, being poor, have only my dreams / I have spread my dreams under your feet / Tread softly because you tread on my dreams"

"I had this thought a while ago / 'My darling cannot understand / What I have done, or what would do / In this blind, bitter land"

Sunday, August 11, 2013

Free of doctrinal baggage

I suppose it's impossible to curate a blog that casts a penetrating eye on a city blighted by centuries-old sectarian hatreds and never explore matters of religious doctrine and faith. So here we go ... Two recent essays analyze the notion that individuals heavily immersed in religion suffer from a dearth of creativity. From Rod Dreher's piece:

How does all of this apply to Van Morrison? Well, the singer-songwriter was raised by an atheist father and a mother whose dalliance with the Jehovah Witnesses was attributed more to a quest for self-improvement rather than atonement for her soul. ("I wouldn't describe my mother as religious," Morrison said. "I think that would annoy her. She's a free-thinker.") Morrison was raised without the doctrinal baggage countless others from Belfast carry. His faith was rooted in a passion for creative thinking and self-expression, rather than narrow creeds and dogma. Outside the confining perimeters of religion, he pursued the belief that one can be wholly spiritual without being fiercely devout. Astral Weeks is a brilliant testament to this.

"I saw so many Catholics and Protestants for whom religion was a burden," Morrison once observed. "There was enormous pressure and you had to belong to one or the other community. Thank God my parents were strong enough not to give in to this pressure."

We live in a time and a place in which people with creative gifts are enveloped by an ethos of expressive individualism, a way of seeing the world that rejects accepting the disciplines of religion and tradition, and poses them as threats to creativity—which, for the artist, means a threat to his sense of self.Of course, Dreher does write in generalities (as does the author of the other essay I linked) and is quick to deliver the caveat that there are obviously creative types who use their hands to clasp prayer beads just as often as they use them to work with clays, and that embracing atheism will not punch your ticket to the Met. Nonetheless, both writers draw conclusions that I find myself arriving at whenever I infrequently contemplate what sparks creativity and what stymies it. Creativity thrives on confrontation, curiosity, and change. Creativity embraces what's prickly and strange, and in extraordinary instances, what's dangerous. Creativity flourishes when a particular kind of emotional responsiveness to the world—one that's pure, impartial, and a tad sophisticated—is not only permitted, but encouraged. The religious mind? It can offer resistance to the influences detailed above. It's a product of static restrictions and tightly-held covenants and a colorless stability where no questions are asked. Religion is wonderful at encouraging a rather empty single-mindedness. I'm reminded of a quote by a German theologian and philosopher named Meister Eckhart: "If you focus too narrowly on a single path to God, all you will ever find is the path."