Sunday, June 30, 2013

Doing geeky things

There are few things I enjoy more than opening a record I just received in the mail. Calling me a geek would be an insult to geeks everywhere.

Monday, June 24, 2013

Personal dispatch #2

This is a dispatch from Kelly Schirmann, a musician who recorded cover versions of all eight tracks on Astral Weeks. First, Schirmann provided a teeny bit of biographical information.

I grew up in Eureka, California, which is a smallish rural community about 200 miles north of San Francisco on the coast. Most people know it because of the redwoods or because they drove through it once on their way to another place, which is okay. There isn't a whole lot going on there. It's foggy and rainy most of the year. I started playing music there when I was maybe sixteen, probably to combat weather-induced sadness. I taught myself basic chords and song structures so I could provide a background for myself to sing against. I don't remember when I first started singing, but I just remember loving it. Always have loved it; it makes me feel good. I'm 27 now. I make music sporadically, by myself and with others, and have gone through periods of performing live as well. At the moment, I'm making music with a writer I like named Sam Pink. We're called Young Family. I'm also putting together more songs under my solo name, HEADBAND. I currently live, write, record, and make stuff in Portland, Oregon.Now, Schirmann's thoughts on Astral Weeks.

When I listen to this album I can feel it in my whole body. It makes my heart and head hurt. And it makes me feel a hard kind of longing that I both completely identify with and also can't ever put my finger on. I return to it over and over to feel these feelings, but also, I think, to try to figure them out, both within the album and within myself. Plus, as a poet, I appreciate that it's basically a very consistent, continuous, imperfect—but still completely gorgeous—poem set to music. I'm not sure when I first heard it or when it started to really stick, but it reminds me of being 22 and recently graduated and living on a farm in Northern California with my best friend. And of being brand new to the world, and completely terrified by everything and in love with everything and especially with the figuring out of myself within a beautiful and terrifying world. Something about the album is so naive and wise at the same time, which I think we could all probably identify with. I feel like it manages to transcend all seasons and all moods. It feels holy to me in that way.And finally, what went into the recording process:

I recorded this album at my family cabin in the woods of Trinity County, California, about an hour east of Eureka in the mountains. I was 23 years old and it was winter, and the rest of my family had gone to bed. I began around 10 p.m. with the intention of recording the whole thing for my aforementioned best friend (who is also a huge fan), but had no idea how it would turn out or that I would finish it in one sitting. I started at the beginning of the album and played each song in one take, directly into the built-in microphone on my computer. It ended up taking a couple of hours, I think. I remember as I progressed it began to feel more and more like a psychedelic experience. It was late and I was stoned, and the songs are all relatively long, so singing and playing them actually felt pretty physically demanding. I also have a lot of personal attachment to some of the songs over others, so it was interesting to form connections with all the tracks and all the lyrics. When I finished, it felt like I had very abruptly come down from a drug. I did no editing on the final tracks except to add a bit of reverb. And then I burned a few copies to keep and give away to other friends who are fans. When I listen to it now, four years later, I hear so much heartbreak and wanting in that recording, but I think that's a pretty accurate translation of Van's version as well. Overall, though, I covered the album as a gift and completely out of reverence for the original. I hope that comes across in the recording.

God's blind spot

I have never covered another artist's work and have no immediate intentions to, yet when I periodically become absorbed with the notion of doing so, I imagine my approach would consist of clutching the tiny fragments of a song that I adore—an unusual rhyme, a fragile melody turned on its head, the dizzying harmony between two oddly paired instruments, a finger-cramping guitar solo—squeezing them tightly, pressing them up against my bare skin, and assuring myself that while not created by me, these fragments were unquestionably written about me, for me, to me. You can never own an artist's song entire; but you can make these tiny fragments yours.

For me, one such fragment is a rather innocuous line from "Madame George" (then again, this being Astral Weeks, an innocuous word really doesn't exist on the album; like a novelist, Van Morrison makes every word count): "Throwing pennies at the bridges down below." It's a song engrossed with the nostalgic specters that haunt the length and breadth of a particular space—and it awakens my own nostalgic specters.

It was a quarter-of-a-mile jaunt from my Catholic grammar school to my church. I walked this route, back and forth, innumerable times: for mandatory First Friday Devotions; following Lenten morning liturgies; to serve at funerals, my cassock and surplice on a wire hanger slung over my shoulder, walking extra slow to prolong the return to the classroom; for Masses honoring the Virgin Mary, my classmates and I sternly instructed to continually recite the Hail Mary prayer during the short trek; even for secular purposes, as a friend and I were selected in junior high to run daily messages between school faculty and the parish rectory (this was the days before email; a fax machine was presumably outside the school's budget).

The walk—no matter what the reason it was undertaken—was a meager, yet heavily anticipated part of the school day. It became a sanctuary of sorts, albeit a temporary and oftentimes—depending on the elements—slushy and frigid one. Free from the forced idolatry of the altar and the compulsory conformity of the classroom, we were in God's blind spot. He couldn't see our tomfoolery, which was delivered via Wet Willy and with shameful impunity. This included tossing coins (or if you were one of the cretins, depositing saliva) on the freight trains that would pass underneath the bridge along the quarter-of-a-mile route. Because we couldn't escape to the exotic destinations these trains were ambling toward, something we once held warm in our hand or pinched tight between our fingers or kept close in our pocket had to suffice. We imagined faraway children with our same gapped smiles and bright eyes finding our pennies. A vision, I suppose, that only those truly tightly bound to a particular spot can fancy.

Tuesday, June 18, 2013

Personal dispatch #1

The fans are composing personal dispatches. Fans of a certain eight-track, 46-minute album; not fans of our infrequently visited headquarters here. This from Jonathan Bernstein, who expounded a bit on the obsessive loyalty Astral Weeks frequently inspires.

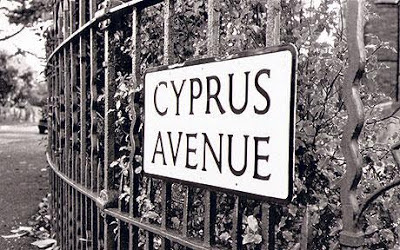

I've been listening to Astral Weeks (on and off, consistently, like you say) for about seven years, since I was, roughly, a junior in high school. I think your blanket statement is quite right: it's a very tough album to be a casual, distanced fan of, and I think you could argue that any casual fan of the record has perhaps never really heard the record, has never dove in and spent a few hours, days, weeks, decades, with the record, like so many of its obsessives have. Astral Weeks is too strange, too full of bleeding hurt to be a casual fan of. It's the type of record where if one of the songs come on when you're at a party, or in your car with friends, or in general with other non-obsessives, it makes you (or at least me) anxious: how is anyone else able to carry on with conversation while "Madame George" is walking around Cyprus Avenue? And so, it's a very personal record for me, and I'd imagine for many or most others. At the risk of cliche, I keep returning to the record because I've never heard anything else like it, because when I was a high school kid, the record opened as many, perhaps more, doors for me than any other. I had no idea what was going on in most of the songs (still don't), but Van's singing, and the cryptic stories he was telling, and the incredible, twisted backing band playing on the record, it was all I needed at 16. I remember walking to school on my own little tree-lined Cyprus Avenue with my headphones, blaring the title track (my walk to school usually lasted the duration of the song) and feeling like I had been given this great big secret no one else had access to. Astral Weeks has that effect on you, you never stop chasing it, or at least I haven't. I took a bus to Washington, D.C., during a college summer break to see Van play the record in full, and I remember walking out of Constitution Hall with that same feeling, like the world had just been briefly ripped open and made more alive. I chased Astral Weeks a few years later as well, when I visited a few friends studying abroad in Belfast and made them spend an afternoon taking a bus to East Belfast to see Van's old haunts. I walked around Cyprus Avenue for a while, perhaps looking for some divine answer as to how this record could have ever possibly been created. Instead, I just got a pretty suburban tree-lined street. I'm looking forward to the next place this album one day takes me.

Wednesday, June 12, 2013

Tilting my head back

Here is Greil Marcus ruminating on Astral Weeks. This was from his rather underwhelming and error-prone book on Van Morrison, When That Rough God Goes Riding:

It was forty-six minutes in which possibilities of the medium—of rock 'n' roll, of pop music, of what you might call music that could be played on the radio as if it were both timeless and news—were realized, when you went out to the limits of what this form could do. You went past them: you showed everybody else that the limits they had accepted on invention, expression, honesty, daring, were false. You said it to musicians and you said it to people who weren't musicians: there's more to life than you thought. Life can be lived more deeply—with a greater sense of fear and horror and desire than you ever imagined. That's what I heard at the time, and that's what I hear now.Quick aside: Marcus' 20-page treatise on Astral Weeks—essentially the lone reason I purchased the book—left me unsatisfied upon the initial read, but became more thought-stirring upon subsequent ones. He references Bob Beamon's Olympic record-shattering long jump, which occurred a few weeks before Astral Weeks' November of 1968 release, illuminates the feat with language that could also characterize Morrison's landmark album—"It was an act for which there are no parallels and no metaphors"—and then ultimately attributes both the leap and the LP's singular greatness to a confluence of fortuitous events. (For Beamon, it was a favorable tailwind and Mexico City's high altitude. For Astral Weeks, it was Morrison being granted a temporary residency at the Catacombs in Boston and producer Lewis Merenstein first hearing a rough cut of the album's title track, and allegedly breaking down and weeping.) Back to the excerpt blockquoted above ... When I listen to Astral Weeks—or, to take a step back, sample other pieces of art considered at or near the pinnacle of their particular medium—I am reminded of childhood trips to Boston and how after walking to Copley Square I would stand at the base of the John Hancock Tower, the city's tallest skyscraper, and tilt my head back until my neck burned with pain and run my eyes along the structure's liquid surface, ever upward, until they reached the summit. The exercise left me feeling anxious and mildly threatened, inspired and euphoric. Astral Weeks is like a gleaming, towering monolith, a choice example of how when pop music brazenly disregards all boundaries, reaches up and grasps the seemingly unattainable, elicits a wide range of emotion reactions—how when pop music accomplishes all this, we, the listeners, are left feeling awestruck and humbled and maybe even swayed—just a smidgen, possibly a bit more—into believing that before we have departed this world we will produce our own tiny masterpieces.

Wednesday, June 5, 2013

"I'm a working man in my prime cleaning windows"

I doubt I will generally get this topical here, but upon reading this story I instantly thought of Van Morrison's 1982 track "Cleaning Windows." This is so shameful you almost have to snicker.

Hundreds of thousands of pounds have been spent on a Fermanagh facelift as the county prepares for the G8 summit in just under three weeks’ time, but locals complain the work paid for by the local council and the Stormont Executive is little more than skin deep.

Two shops in Belcoo, right on the border with Blacklion, Co Cavan, have been painted over to appear as thriving businesses. The reality, as in other parts of the county, is rather more stark.

Just a few weeks ago, Flanagan's – a former butcher's and vegetable shop in the neat village – was cleaned and repainted with bespoke images of a thriving business placed in the windows. Any G8 delegate passing on the way to discuss global capitalism would easily be fooled into thinking that all is well with the free-market system in Fermanagh. But, the facts are different.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)