Sunday, September 29, 2013

Muted lamp light

Just as there's something warm and wonderful about listening to vinyl in the shadowy isolation of your bedroom, so too is there something generously pleasurable about recording a cover song on your own turf. Muted lamp light, a tightly closed door, a large, empty water bottle looking forlorn on a dresser. Refraining from shifting on the bed that way the box spring's creaks and groans don't find their way onto the recording. Keeping your vocals hushed and your strumming softened so as not to wake those who are slumbering. Feeling relief when the cover is finished because you've gotten out everything you had bubbling inside you.

Thursday, September 26, 2013

Cross-generational allure

Author Greil Marcus, one of Astral Weeks' most distinguished and ardent supporters, once discussed the album's power to transcend its era. While teaching at Princeton University, Marcus handed out questionnaires, asking his class to list their favorite books, movies, and albums. Of his 15 students, four selected Astral Weeks.

From a 2010 interview with Marcus regarding his book, When That Rough God Goes Riding: Listening to Van Morrison: "Now these are people who were born in the late eighties, twenty years after the album had been released. It's conceivable their parents weren't even born when the album was released. And yet this album had found them, or they found their way to it."

Of course, Marcus' evidence of Astral Weeks' cross-generational allure is purely anecdotal. However, it's not too far-fetched to contend that a particular subset of today's teenagers and 20-somethings are devotees to the album, simply because the Internet has allowed music listeners, adolescent and aged, to enormously expand their palettes and become easier acquainted with artists from formerly out-of-reach time periods, genres, cultures, and so forth.

What I'm curious about is how young audiences initially react to Astral Weeks or more specifically, what they think about the sheer density of its content. During my first listening experiences I found the album to be near impenetrable, both sonically and lyrically (gee whiz, more anecdotal evidence?). Astral Weeks was a tightly-guarded fortress; no matter how many times I assailed its walls, I could never reach its heart. Growing up, my exposure to Van Morrison was restricted to my parents' playlists, which leaned heavily on radio staples, Into the Music, and scattered offerings from his '90s oeuvre. I couldn't believe Morrison was capable of such startling—yet mildly bewildering—complexity.

So what do young audiences think? I pose this question because of what I've been told regarding the behavior of Millennials—those individuals born between (give or take a few years) 1980 and 2000. "Connected" does not begin to describe their life experiences; "hyper-connected" is more apt. They are early adopters of new technologies and passionate users of texting, emailing, and social networking. They are characterized as having short attention spans, relentless preoccupations with multi-tasking, and exhaustive appetites for information. One story I read humorously diagnosed Millennials with AOADD: Always-On Attention Deficit Disorder.

Wall Street Journal critic Terry Teachout wrote about how modern theater would benefit from a more improved effort to win and sustain audience attention: "The leisurely expositions of yesteryear, it turns out, aren't necessary: You can count on contemporary audiences to get the point and see where you're headed, and they don't want to wait around for you to catch up with them." Could the same be written about music that's uncompromising and challenging? About Morrison and his nearly 10-minute long opus "Madame George"—or Astral Weeks' three other tracks that clock in at over seven minutes long?

Of course, this is all unfair. Characterizing an entire generation is eternally misguided. One also can't presume that Millennials approach art in much the same way they approach Facebook news feeds, posts on Tumblr, or Google search results. The Internet may have slightly eroded our ability to remain focused, but I like to believe it hasn't spoiled our appreciation for art, particularly that which tests our patience and stamina. Because ultimately, the payoff from such art brings the most satisfaction.

From a 2010 interview with Marcus regarding his book, When That Rough God Goes Riding: Listening to Van Morrison: "Now these are people who were born in the late eighties, twenty years after the album had been released. It's conceivable their parents weren't even born when the album was released. And yet this album had found them, or they found their way to it."

Of course, Marcus' evidence of Astral Weeks' cross-generational allure is purely anecdotal. However, it's not too far-fetched to contend that a particular subset of today's teenagers and 20-somethings are devotees to the album, simply because the Internet has allowed music listeners, adolescent and aged, to enormously expand their palettes and become easier acquainted with artists from formerly out-of-reach time periods, genres, cultures, and so forth.

What I'm curious about is how young audiences initially react to Astral Weeks or more specifically, what they think about the sheer density of its content. During my first listening experiences I found the album to be near impenetrable, both sonically and lyrically (gee whiz, more anecdotal evidence?). Astral Weeks was a tightly-guarded fortress; no matter how many times I assailed its walls, I could never reach its heart. Growing up, my exposure to Van Morrison was restricted to my parents' playlists, which leaned heavily on radio staples, Into the Music, and scattered offerings from his '90s oeuvre. I couldn't believe Morrison was capable of such startling—yet mildly bewildering—complexity.

So what do young audiences think? I pose this question because of what I've been told regarding the behavior of Millennials—those individuals born between (give or take a few years) 1980 and 2000. "Connected" does not begin to describe their life experiences; "hyper-connected" is more apt. They are early adopters of new technologies and passionate users of texting, emailing, and social networking. They are characterized as having short attention spans, relentless preoccupations with multi-tasking, and exhaustive appetites for information. One story I read humorously diagnosed Millennials with AOADD: Always-On Attention Deficit Disorder.

Wall Street Journal critic Terry Teachout wrote about how modern theater would benefit from a more improved effort to win and sustain audience attention: "The leisurely expositions of yesteryear, it turns out, aren't necessary: You can count on contemporary audiences to get the point and see where you're headed, and they don't want to wait around for you to catch up with them." Could the same be written about music that's uncompromising and challenging? About Morrison and his nearly 10-minute long opus "Madame George"—or Astral Weeks' three other tracks that clock in at over seven minutes long?

Of course, this is all unfair. Characterizing an entire generation is eternally misguided. One also can't presume that Millennials approach art in much the same way they approach Facebook news feeds, posts on Tumblr, or Google search results. The Internet may have slightly eroded our ability to remain focused, but I like to believe it hasn't spoiled our appreciation for art, particularly that which tests our patience and stamina. Because ultimately, the payoff from such art brings the most satisfaction.

Monday, September 23, 2013

Instrumental cuts

Wu-Tang Clan and Van Morrison ... Where can we draw parallels? Well, both are deeply indebted to a specific place: For Wu-Tang, it's Shaolin/Staten Island; for Morrison, Belfast. Unearthing further correlations would mean citing falsehoods and misrepresentations and other assorted bullshit. Let's not do that. Instead, let's click on the above link. It features instrumental cuts of the best tracks from Liquid Swords. With the vocals pared away, the listener is allowed to fully appreciate the album's toxic beats. Your ears will ripple and shudder with orgasm.

I wish some industrious YouTuber would do the same with Astral Weeks. I'm aware that such a request is borderline blasphemous. Morrison's vocal performance is nothing short of transcendent; he "plays" his voice as masterfully as any of Astral Weeks' session musicians play their instruments.

But at the same time, how else could we wholly cherish: the swelling strings on "Sweet Thing" and how they melt into the heartbeat of Richard Davis' double bass; the sprightly harpsichord in "Cyprus Avenue" or how in the same track, Davis' bass lines gloriously enliven empty spaces; the wistful sound of Morrison strumming the G, C, and D chords to open "Madame George; the hiss of Connie Kay's hi-hat and the humming dirge of the cellos in the same track; or the shivering, itinerant soprano saxophone in "Slim Slow Slider."

Wednesday, September 18, 2013

Baa, baa, black sheep

A decade ago, music writers began penning obituaries for the traditional album cover, citing its relegation to postage-stamp dimensions on mp3 players or its frequent total absence when a release was downloaded illicitly. This was the terminus for a gradually shrinking medium—the end point for a reduction that commenced when vinyl waned in popularity, and the 12-inch-by-12-inch canvases once used by artists and record companies gave way to the centimeters worth of tiny space offered by cassettes and compact discs. Album art, we were informed, was poised to become less creative, less conspicuous, more utilitarian, a mere label for the music product it was packaging.

These requiems were a bit premature. Vinyl staged a bit of a rally. Meanwhile, music became instantaneous and ubiquitous, the sheer amount of musicians yearning to be heard seemingly infinite. And that means photography, typography, and graphics that are eye-catching to consumers—even when using that significantly miniaturized canvas—can still rank as crucial components of an release's success.

What does the album cover's small revival in importance mean for Astral Weeks? Primarily this: Its rather second-rate artwork will continue to perpetuate the myth that Van Morrison functions as some sort of hippie troubadour, that the music of Astral Weeks is the ideal soundtrack to druggy experimentalism and cliched attempts at transcendence. It's a myth that's existed since the album's release 45 years ago. From Steve Turner's Too Late to Stop Now:

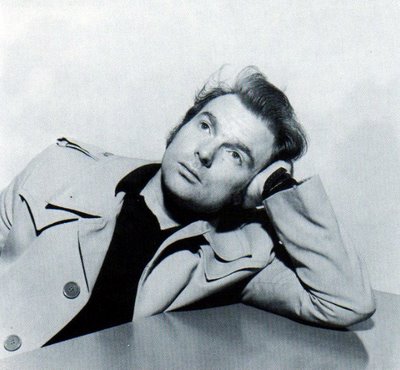

For many people at the time Astral Weeks perfectly articulated the experience of the acid trip, with its invocation to be born again and its subsequent journey through layers of childhood experience in flashback sequences. It became one of the essential albums for travelers on the "hippie trail" from Europe through to Kathmandu, and there were even reports of vans painted in psychedelic colours being renamed "the Van Morrison."If you're reading this blog, you're certainly familiar with the album's cover, and the hallucinatory and gauzy—yet at the same time, hackneyed—vibe it emits. The photo, as well as the absurd poem printed on the insert, was intended to compliment the album's themes of otherworldliness, nostalgia, youthful passion, devotion to place, etc. Instead, the art feels embarrassingly unimaginative, slightly anachronistic, even off-putting (all that green and black; ick)—essentially everything that is the antithesis of Astral Weeks. When Morrison's lifted-from-an-adolescent-diary poetry isn't eliciting a giggle ("When I got back it was like a dream come true"), it has you scouring the Internet for lewd jokes ("Loved you there and then, and now like a sheep"). In the photo, a disoriented-looking Morrison stares downward, possibly at his hands or his shoes or his acoustic guitar (or a sheep). And have I mentioned the green-and-black color scheme? Warner Bros. did have good intentions when it was developing the album's artwork. The photograph was snapped by Joel Brodsky, a notable New York photographer credited with shooting the hard-to-imagine total of 400 album covers. Interestingly, Brodsky photographed a number of moderately successful bluesmen—Buddy Guy, Otis Spann, John Lee Hooker, and Junior Wells, to name a few—a fact that would have certainly thrilled the blues-obsessed Morrison. His more well-known clientele included Joan Baez, Kiss, the Stooges, and the MC5. And oh yes, he also did this photograph, a staple of any white male college student's dorm room. There is certainly worse album art in the Morrison discography. And when one considers the packaging of other iconic albums from the late '60s, Astral Weeks' faults don't appear so egregious. There's also this: The release's eight tracks transcend its packaging. As avid listeners can attest, spend a bit of quality time with Astral Weeks and you eventually recognize that the hippie troubadour/experimentalism/drug motifs cited above are misguided at best, disingenuous at worst.

Monday, September 16, 2013

Shaking the stalagmites from my tongue

We chat about music, but I typically do most of the chatting. Fueled by great tumblers of drink, which shake the stalagmites from my tongue, and a passion that goes from smolder to blaze when I'm in the presence of others similarly devoted to consecrated acts of music consumption, my words are, simply and unabashedly, endless. One night you spluttered, and my first thought was this was the act of a man drowning in talk, a man coming up for a breath of air, desperate to be rescued by the very individual who was drowning him. Only you had tipped your glass back for a drink and the liquid funneled down the incorrect pipe. I delivered several sharp blows to your back—and then continued chatting.

One summer, in the dimly-lit and dust-touched sitting room of a faraway vacation home, I prattled on about Jason Pierce and how his songwriting veers toward the embarrassingly honest and how frequently his candidness includes drug-related confessions that are blunt and rhapsodic, and as I classified them as "art" and "artful" and "art created by an individual sacrificing himself for art" I couldn't help but wince, because they also feel like a cluttered, detached addict merely wishing to celebrate his gutter-worthy position as a cluttered, detached addict. Your confidence in my mental health was shaken a little; I could tell, even if you didn't vocalize it. But really, how much joy can truly be derived from a passion—even if that passion is druggy songwriters—when it's sealed away inside you?

I'm not always playing the role of incessant talker; occasionally I am a vigilant listener. There was a night where a large party was whittled down to just the two of us. We sat on the couch with drinks, playing deejay on iTunes, the clock on the wall making slow progress toward some ungodly hour. I clicked on "Ballerina" and you talked. The standing-in-the-doorway moment—you loved that. Van Morrison perched on a threshold, a lifetime of decisions bringing him to this very specific moment, a decision of a lifetime waiting to be made. "He's smitten," you kept declaring. "Smitten."

We said the word over and over until it no longer even sounded like the word—or any word, for that matter. It was just a sound, all soft s's and crisp t's. Maybe we were subconsciously taking a cue from Van Morrison. Maybe incantations of the word permitted us to fully grasp and appreciate "Ballerina"'s climax. Maybe we were drunk.

In any case, I suddenly felt like a transaction took place between us, in which you and myself and Astral Weeks were now on one side, and life was on the other, and that side was always trying to get the better of us, and occasionally we rumbled toward a confrontation, but without fail and without losing too much skin, we held off every advance.

Wednesday, September 11, 2013

Personal dispatch #7

This is a dispatch from Marty Rod, who recorded a smoldering, gauzy, reverb-drenched rendition of "The Way Young Lovers Do." His cover is like watching a cigarette slowly burn a crisp, black hole in a bolt of silk. Rod told us a little about himself, as well as why he selected this particular track from Astral Weeks.

I was born and raised in Reseda (popularized by Tom Petty and The Karate Kid), which is in Los Angeles suburbia. I'm 26 years old and have been a professional musician, at least in terms of making a living off music, for the past two years. I started singing before I could remember. I started playing guitar at 12 and was writing songs by 16. I think that in today's music industry being multi-dimensional is a necessity to staying active and establishing a career. To that end, I started learning multiple instruments and consuming knowledge on production and recording ever since I was in college. Now I often record and mix many of my own songs. I've done numerous productions for other artists as well as TV shows and films. I perform with my band and my pet project, Bravesoul, mostly here in the Los Angeles area. I also do acoustic performances in Venice at the Wizend one to two times a month. I've always been a huge fan of Van Morrison. I was a bit older when I first heard some of the songs off Astral Weeks—most likely in college at some point—and I must admit, I didn't really "get it" at first. I think I had heard "Sweet Thing" and "Madame George" on a road trip and thought they were cool songs, but I didn't really connect with them. I think growing up in a generation that's entirely focused on mp3s and singles, it took me a long time before I realized the difference between a compilation of songs and a true album. Astral Weeks is definitely a true album and it was an eye-opening lesson in that respect. It's something that should be heard in its entirety. Only then can you really enjoy the improvisational and fluid arrangements, and the pure childlike emotions that seem to grow stronger from song to song. It's more of an experience that needs to brew and be felt, rather than a three-minute espresso shot of energy and catchy hooks. "The Way Young Lovers Do" was one of those songs I heard while listening to the full album. The lyrics immediately moved me. It's not an uncommon theme by any means, but I loved the delicate and innocent way he painted the scene. It was so simple and direct, and the song seems to transport you to a different time and space. It also seems to stand out from the rest of the album both in its simplicity and its more traditional form and structure. In hindsight, that no doubt may have also been one of the reasons I initially gravitated towards that song. I wanted to cover the song for the same reason i think you should cover any song: I thought I could do it a bit differently. Songwriters like Van Morrison or Bob Dylan are always great fodder for covers because they have very distinctive voices/styles and their songwriting is amazing. In other words, it's not hard to sound different. And the lyrics and melody give you a powerful foundation to pretty much take the song in many directions. In my mind, I wanted to take the song more into the spaghetti western world and make it more of a full-on cinematic experience. I decided to make it a duet for that same reason as well. I recorded everything in my living room here in west L.A. I brought my good friend and writing partner Jacqueline Becker on board to lend her beautiful voice and make it a duet. The recording and mixing process literally took no more than a single day. It just took a stroke of inspiration and within about eight hours it was all done.

Friday, September 6, 2013

A meticulously considered approach, aesthetic, and atmosphere

Mike Powell, who is one of my favorite music critics born during the compact disc era, recently launched a column named "Secondhands" for the popular music site Pitchfork. It examines, according to the introduction on the first "Secondhands" entry, "music of the past through a modern lens." Okay, so as far as mission statements go, that one's rather terse and ambiguous. When it comes to substance, however, Powell is anything but.

The latest "Secondhands" piece covers Astral Weeks. Aside from an occasional bout of hyperbole ("Nobody who played on the sessions for Astral Weeks has anything nice to say about the experience") and a closing paragraph that feels tacked-on, the piece deftly illustrates why the album resonates with a particular subset of listeners (including Powell).

... The artist as someone who is not well-rounded, who is not capable of seeing all points of view or transcending the confines of their own perspective—basically, the myth of the artist as someone who has yet to transform from a child into an adult.Then there's this:

Audiences can appreciate this myth because they've probably experienced flashes of romantic single-mindedness, too. But it's also that life—in its variety and responsibilities—doesn't give us much room to be single-minded, and so we need to step sideways into the parallel universe of art, where we're allowed to feel those narrow teenage feelings for as long as the album lasts.Powell's reference to a particular single-mindedness hints at what I feel is one of the principal reasons Astral Weeks is so extraordinary: There was a fascinating dichotomy at work during the album's three sessions. Even though lyrics flowed stream-of-conscious-like and the assembled musicians were instructed to play "whatever they felt like playing" (per drummer Connie Kay), Morrison was strictly devoted to a meticulously considered approach, aesthetic, and atmosphere. Astral Weeks is metamorphic, fluid, and loose—all because months of refining the material at his parents' home in Belfast and the Catacombs in Boston gave him a rather rigid and precise vision of how the album should sound. Astral Weeks is formless by virtue of its stringent form. (In typical Van Morrison fashion, the singer-songwriter later claimed that the finished Astral Weeks product didn't quite meet his expectations. "I didn't really get into it as much as I thought I would," he claimed. Also: "I was kind of restricted, because it wasn't really understood what I really wanted.")

Wednesday, September 4, 2013

Frayed memories / memories are frayed

Still scouring the Internet for information on the Catacombs, the Boston club where Astral Weeks took its first sharp breaths, where Van Morrison collaborated with a pair of Berklee College of Music students—upright bassist Tom Kielbania and flautist/saxophonist John Payne—before New York City and Century Sound Studios beckoned.

Harry Sandler, co-founder of the Music Museum of New England and one-time drummer for the band Orpheus, provided me with a bit of background. Carl Tortola, webmaster for the museum, recommended I get in touch with Joe Viglione, who was involved with the Boston music scene in the '60s and '70s. Joe linked me to a gig poster for the J. Geils Blues Band. The group performed at the Catacombs during January of 1968 (Morrison and company played that summer). However, Joe had little else to offer other than names. One was Rick Harte, who responded to my query with this:

Hi, Ryan. I remember going there. It was down several flights of stairs. I didn't go there much. But it's true: Van Morrison lived in Cambridge for a long time. On Green Street, Kirkland, or Kneeland. I'm a huge fan of Them and the early Van Morrison solo years. While I was around then and would see him, it's still way over 40 years ago and memories are frayed.Another contact, Jason Brabazon, was also contending with frayed memories:

It's funny (peculiar), a lot of times, even tho' I'm sure I remember where something (in Boston; music-related or otherwise) used to be, it turns out my memory has failed me. I was certain I remembered where the entrance to Paul's Mall & the Jazz Workshop was, but when I found an old ad showing the Boylston St. address, I was way off! I think (in retrospect) that I was in fact remembering where the Unicorn Coffee House used to be. When I was a kid (single digits), my mum and her friends used to talk about this sort of thing (like where Scollay Square used to be or such-and-such a restaurant before they tore it down) and I remember thinking: I'm glad I'm not so old that my world has evaporated around me. But now, here we are ... I'm sorry I can't be of more help. I was around when he lived here (Green Street), but it's not like we hung out or anything. I remember him playing a free concert on Boston Common and singing "Rain, rain, go away." I think to the tune of "Ro Ro Rosey." I may still have the flyer somewhere. It was billed as the "Van Morrison Project" or something like that. At first I wasn't even sure it was really the actual guy. I thought it must just be the name of some band; like if you saw a billing for a band called the Bela Lugosi Initiative, you wouldn't expect it to actually be the Bela Lugosi. And what would someone as big and famous as Van Morrison be doing playing for free?So I soldier on ...

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)